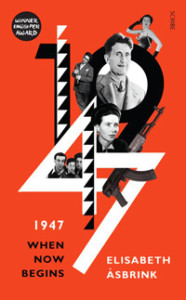

1947: When Now Begins

by Elizabeth Asbrink

Published by Scribe scribepublications.co.uk

These are difficult times. Huddled refugees flee countries riven by war. Religious intolerance turns brother against brother in paroxysms of violence. The spectre of terrorism haunts the world and resurgent racism we though long defeated rises up to spew old hate in new voices.

The book title might give a clue that the difficult time I’m referring to is not our present predicament but rather some 70 years in the past. ‘1947: When Now Begins’ by Swedish journalist Elizabeth Asbrink (translated by Fiona Graham) is part history, part biography, part philosophy that– if I may be permitted an old reviewing cliché – defies easy description. That being the case, I’ll try a difficult description.

History, as tackled by Asbrink, is a bit like Google Maps. There are plenty of histories that allow you to glide over the past at will, scrolling over ancient Rome, the Middle Ages, wars of your choice etc. Asbrink ignores this grand sweep for the temporal equivalent of zooming in to deposit us into a street view of some unfamiliar place buzzing with detail.

Zoom – we’re reading Simone de Beauvoir’s love letters to Nelson Algren. Zoom – Per Engdhal’s underground railway is ferrying SS offices to Argentina. Zoom – Christian Dior finds his ‘new look’ and Vogue magazine banned in Britain. Zoom – the British fleet is blockading Jewish refugees. Zoom – George Orwell almost dies on Jura. Zoom – Thelonious Monk is performing at Minton’s Playhouse. Zoom, zoom, zoom… All of these people building a shared zeitgeist and unknowingly birthing our modern world. It’s easy to think of de Beauvoir reading about Dior’s travails for instance or Orwell listening to news of the blockade on the radio – each individual part of the background action for the other’s personal dramas.

Structurally, the book concentrates on an examination of the single titular year with occasional narrative tendrils sneaking briefly forward and backwards in time for context. Each of the vignettes is followed by hops and skips across monthly chapters which are divided into sections a couple of lines or a couple of pages long. Location subheads of Paris, Rome, Cairo, London etc are still patinated here with the remnants, courtesy of the telescope of time, of a noirish mystique.

The writing is spare but descriptive with the intimacy of pages plucked from a diary (if the diary was written in the third person). Elegant, staccato sentences pepper a commentary more reminiscent of E.E. Cummings poetry than any history book you might have read. Motivated variously by passion or pragmatism, the characters – rather the real people – pivot around events and each other, accreting what we call history but they, for the most part, would have just thought of as living their lives.

Asbrink necessarily ignores vast swathes of history. There’s little about the international finance helping to rebuild the post-war world and almost nothing about the politics of the US or Europe. China’s civil war goes unremarked. The subjects she does cover are not evenly divided either. Far more time is spent on the partition of Palestine than the partition of India for instance. But Asbrink isn’t ‘looking in’ on events, she’s taking us into the private lives of the people looking out. Their street level view is just as narrow and parochial and as intensely personal as our own.

What ‘1947: When Now Begins’ does well is help us place our daily lives and our interesting times in a broader historical context. It reminds us that the people for whom history was headline lived in a world at least as complex and conflicted as today, in many ways far more so. If they persevered and built a better world perhaps we can too.