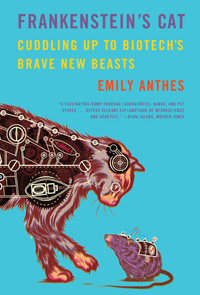

Frankenstein’s Cat

Cuddling up to Biotech’s brave new beasts

by Emily Anthes. Published by Oneworld www.oneworld-publications.com

Remember that episode of the Big Bang where Sheldon created glow-in-the-dark goldfish? Real mad-scientist stuff right? Em, no. Though exaggerated for TV, glow-in-the-dark-goldfish are a real thing. They’re called Glofish and have been sold by Yorktown Technologies through US pet shops since 2004 (except in California – hence Sheldon’s DIY fish).

Animal bioscience isn’t as flashy or immediate as phones or drones but it’s been here a while and it’s growing fast in capability and complexity. In ‘Frankenstein’s Cat’, Emily Anthes kicks our chairs and gets us to sit up straight and pay attention.

With a sliver of sea anemone DNA, GloFish were the world’s first transgenetic pet. They won’t be the last. Fancy a non-allergenic cat or a dog that loves only you? If you have the money, you might even consider getting a clone of your favorite furry companion when they pass on. Cloned farm animals are old hat but cats and duplicate dogs have proved less popular and a lot harder as epigenetic variability (or how the proteins DNA codes for are expressed) means that just copying the DNA isn’t enough – as people gored by the evil-tempered clones of passive bulls will attest.

Cloning prize animals is already a bit passé and ‘pharming’ – tweaking an animal’s genes to turn them into pharmaceutical factories is where it’s at. Squeezing a drug for a rare clotting condition from the teat of a goat sounds like something from a near-future SF novel but ‘Atryn’ was approved by the FDA back in 2006.

Living sensors are another field that is growing fast. From collecting deep ocean data to minesweeping, our furry friends have been recruited into ever more varied roles. Spy organizations have always been interested in bugs but now their bugs are, well, bugs. Cyborg bluebottles with listening devices powered by the beat of their own wings are flying off the drawing boards (sorry, couldn’t resist that one) into bunkers and boardrooms. You don’t need to be DARPA to remotely control animals either. DIY cockroach control kits are available on the Internet. For only a few dollars – and a strong stomach – you can build your own cyber-roach. Will kids hack their pets like you hacked your Sinclair Spectrum or is there, somewhere between ants and apes, a ‘Disney effect’ where animals are too cute to control?

We already use animals by the millions for food and science. Adding a new reproitor of skills – whether it’s robo-pets or organ replacement farms – will condemn millions more to being utility objects. If, with the best will in the world, we engineer animals to feel no pain in factory farms will that just rationalize even worse conditions? The moral dilemmas aren’t explored in much detail but maybe we should be making up our own minds where we stand or, at least, realizing, that there is a stand to be made.

Maybe we can use the same bioengineering to help animals survive in the dangerous new environment they find themselves in – the one with us in it.

Cloning can bring back rare – or extinct – animals. Extending the life and reproductive span of endangered species could mean the difference between extinction and survival. We can restore the sight of Red Setters and fix some of the other physiological handicaps breeders have foisted onto generations of dogs. We can put artificial tales on Dolphins and bionic legs on thoroughbreds and more. Anthes’ last chapter is an optimistic panacea where all the bioscience benefits we want for ourselves – all that fitter, stronger, smarter stuff – we share with our furry friends, elevating them along with us to a better, more harmonious world.

Maybe. Or maybe I’m just cynical enough to think we’ll need to bioengineer a better human being first.