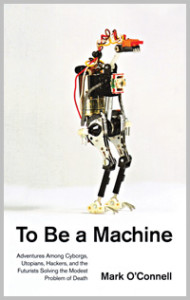

To Be a Machine

by Mark O’Connell

Published by Granta Publications www.grantabooks.com

To see ourselves as others see us is a gift according to Robert Burns and in “To Be a Machine”, author Mark O’Connell gives us that gift. I say ‘us’ here to mean the sort of people who would pick up a book with the subtitle “adventures among cyborgs, utopians, hackers and the futurists solving the modest problem of death”.

Curiously, O’Connell isn’t one of those people. He has a PhD in English Literature (his prose is all elegant allegories and recondite references) and usually writes, well, arty stuff for arty people. “In no sense was this my world”, he says so why is a New York Times literary critic writing a book about transhumanists?

Inspired by the fragility of his new-born son O’Connell admits to a fascination and a certain sympathy for the motivations of the transhumanist movement but he denigrates pretty much everything they actually do or aim towards. He doesn’t have time to worry about the worst case scenarios because he’s too busy being terrified by the best case ones.

But this is the strength of this book – O’Connell’s jaundiced ‘everyman’ take on a subject that’s way too often hyped to the hilt by gosh-wow tech journalists. “ To be a Machine” is a reality-check on a paradigm of technological threat and promise that has snuck upon us almost unopposed. Can we really “transcend the condition of humanity through technology” or is it all just stuff and nonsense? O’Connell goes on a whirlwind tour to find out – from the hopeful dead of Alcor to the DIY cyborgs of the Grinder movement to, frankly, a lot of odd people doing odd things. If, along the way, you find yourself disagreeing with the idea of artificial intelligence destroying humanity being “so childish as to be hardly worth thinking about” is that because he doesn’t have a deep enough grasp of the issues or because you’ve drunk too much of the geek apocalypse Kool-Aid? To be fair, O’Connell himself vacillates – even he can’t be sure if it’s the transhumanists who are crazy or he is. Either way, through O’Connell’s eyes we can take a step back and perhaps see a little wider. Starry-eyed futurism is often funded by military contracts and motivated not by common good but more efficient violence. It’s also amazing how, from certain perspectives, the new ideas of technological utopia resemble re-packaged old ideas – religion for those unable to believe in a god.

The ‘innocent abroad’ approach does have drawbacks though. There is a whiff of PT Barnum and carnival freak-show about the way O’Connell parades the colourful cast of characters from the transhumanist circus. He’s not writing about the ideas so much as the people who have the ideas. Actually, for the most part, he’s writing about the people who follow the people who have the ideas – the kooks, not the chefs. Laura Deming, a brilliant MIT researcher exploring serious life extension technology gets 3 pages, Zontan Istvan driving a coffin shaped RV across the states in his presidential bid gets 30.

O’Connell’s lack of background in the sciences shows at times too. For example, a casual mention that all the body’s cells are replaced every 7 years merits a researched footnote rejoinder – neural cells are (mostly) for life. Well yes. You know that, I know that, pretty much anyone who might have an interest in reading this book knows that. It’s obvious from context that the interviewee knew that and probably assumed O’Connell did too. That he clearly didn’t makes you wonder what other nuances have slipped through the illusion of a common language.

Overall though, despite the cynicism – actually, because of the cynicism – ‘To be a Machine’ offers a fresh perspective on the debate and sets the all too human players of the transhumanist drama on a bigger, older and more familiar stage.