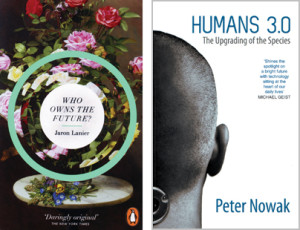

Who Owns the Future

by Jason Lanier

Published by Penguin www.penguin.co.uk

&

Humans 3.0

by Peter Nowak

Published by Harper Collins www.harpercollins.co.uk

“What’s to become of us?

What becomes of people when their civilization breaks up? Those who have brains and courage come through all right. Those that haven’t are winnowed out.

Don’t stand there talking nonsense at me when it’s us who are being winnowed out!”

Vivian Leigh – Gone With The Wind

Over the last ten years I’ve watched the newspaper industry dissolve around me like a sugar cube in hot coffee. Photographers, travel agents, video rental and record store owners are in the same boat and people who drive for a living may be climbing aboard over the next decade. MIT researcher Andrew McAfee estimates that new technology is destroying old jobs faster than creating new ones and ‘Wired’ predicts three quarters of human jobs will be replaced by machines this century (as I write this, Foxcon – the company that makes iPhones – just replaced 60,000 workers with robots). So what is to become of us?

This is the question that Peter Nowak and Jason Lanier separately raise and try to answer in ‘Humans 3.0’ and ‘Who Owns the Future’ respectively. Nowak has been an award winning tech columnist and blogger for 15 years. Lanier is a middle aged musician, hacker & researcher who sold start-ups to Google while shooting the breeze with Marvin Minsky and William Gibson.

It would be easy to caricature these two takes on an impending information dystopia as youthful optimism versus grizzled experience so I will. That’s far from the whole story of course but Nowak is definitely more bullish (almost Pollyanna-ish) about future prospects. Lanier seems to have a deeper grasp of the issues, but it’s always easier to seem wise delivering bad news.

Despite what Lanier refers to as his ‘counterculture hair’ (he looks more likely to share a spliff than a socio-economic theory) he is very much in favour of big business – there’s some things you just can’t Kickstart – and against ‘free’ information. Free information services (what he refers to as ‘Siren Servers’) trapped us in a downward spiral where humans have become “essential but worthless”. We’re breaking down the old levees he says – the barriers put up by industry and unions – without building new ones. Those barriers may have seemed like protectionism to people trying to get a start (and they were) but they were also safeguards. The free internet is a fine place he says, as long as you don’t get sick or old or have a family. It’s not just the little people who suffer either. Concentrating information with an “all for us and nothing for others” philosophy may make individual billionaires but shrinks the overall economy.

Nowark recognises the same problems as Lanier – such as half the population of his home city of Toronto being in insecure, benefitless ‘precariously employment’ – but mostly as a brief precursor to proposed solutions. He stakes his money on ‘combinatorial development’ – the ability of individuals to constantly combine the possibilities supplied by new technology in every increasing variety. Our problems, he suggests, will come not from a lack of solutions but a failure to imagine them. Take Kodak and Instgram for instance. Kodak is almost gone but Instgram – an 18 month old startup – sold to Facebook for a billion dollars. That’s technological entrepreneurship!

Entrepreneurship is something Nowak is keen on. Replace ‘technological entrepreneur’ with ‘small business entrepreneur’ and he would sound a bit like an 80’s Thatcherite when singing the praise of Israel’s venture capital and startup tradition and Canada’s shift to a ‘culture of individualism and self-betterment’. Fully a third of new businesses in Canada are expected to succeed he writes but doesn’t address the two thirds who fail, loosing their shirts – or somebody’s shirts – in the process. Never mind says Nowak, “Inequality looks as though it will reach a natural limit before self-correcting mechanisms take effect” but doesn’t offer any hint of what that ‘natural limit’ might be. Nor does he seem to realise that historically the ‘self-correcting’ mechanism has taken the form of a blood-thirsty (and probably shirtless) mob storming the Winter Palace.

In contrast, Lanier’s solution is systemic – a two way internet where the value Google et al extracts from your personal data is paid for rather than appropriated with a micro payment winding its way back to you whenever some big data server crunches your numbers for profit. Paid information and symmetrical commercial rights where nothing is free but everything is affordable is necessary to stop the current erosion of the middle class he warns. Take Kodak and Instgram for instance. Kodak employed 140,000 people at its peak and while Instgram might have sold for a billion dollars they employed just 13. Not 13 thousand, 13 individuals. Nowak’s ‘plucky entrepreneurs’ who add thousands of jobs to the market are fine, suggests Lanier, but the technology they leverage is costing millions of middle class job. That’s bad for everybody because ultimately that’s where customers come from.

Nowak’s up-beat prose is peppered with pop culture references and repeated phrases like ‘it’s happening now’ and ‘whopping’. The breathless gee-whizzery makes ‘Humans 3.0’ feel shallow but there’s a lot of solid journalism. We hear from a variety of folk working right at the coalface of technological and social change from Microsoft think-tanks and Ashley Madison’s CEO to privacy campaigners and Buddhist app makers. Lanier’s style has more depth but while his two-way internet is by far the more radical solution I don’t know how workable it might be. A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that, for the ordinary Joe, those micro payments would be pretty darn micro. Still, it’s a work in progress as he readily admits.

Maybe Larry, Sergey and Mark can stop chasing the same shrinking pool of advertisers and lead the phase change in the economy Lanier thinks we need. We might have to wait till the Baby Boomers, Generation X and even the Facebook Generation are dead and gone but Lanier is convinced we can adjust even if it takes a century. Nowak is equally confident but on a shorter time scale. We’ve faced challenges like these before, he says and innovated our way, not just out of danger but to pastures greener than we had previously imagined. Nowak’s relentless optimism could definitely do with some of Lanier’s more grounded perspective but a leavening of can-do problem solving wouldn’t hurt Lanier’s sober analysis either.

For Lanier it’s all about the system, for Nowak it’s all about the individual but both authors would probably agree that if we use our heads rather than sticking them in the sand, maybe no one need be winnowed at all.